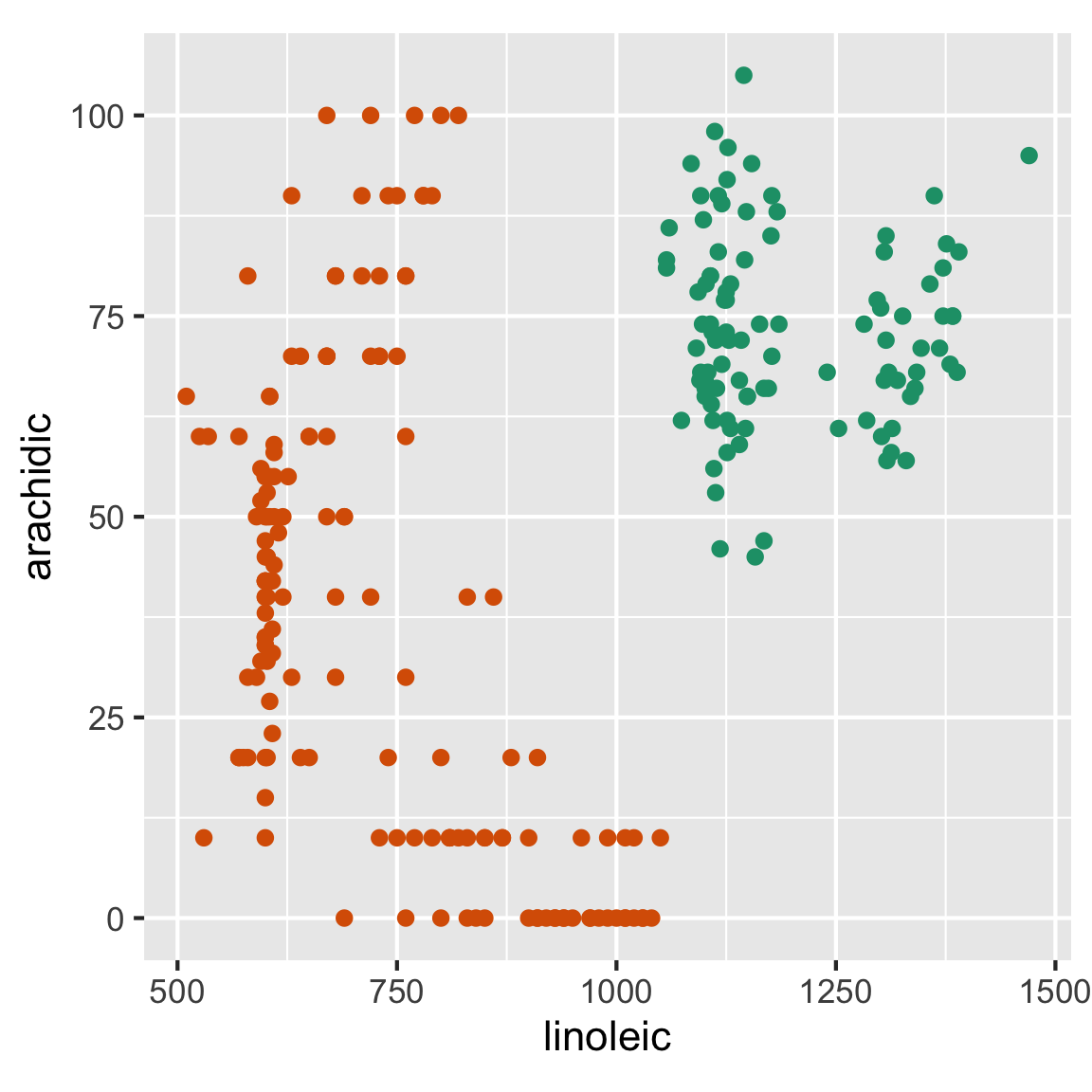

There are two ways to approach this problem. You can either find a line that separates the groups into two mounds (similar to what was done in lecture 2), or you can find a line that can be used as a decision boundary to separate the two groups (so each group is entirely contained on one side of the line). The line that is perpendicular to that decision boundary will be a good projection to separate the groups. The line that separates the two groups is what you want to project your data onto.

You can either manually calculate this line by looking at the plot and finding the slope with the visualisation. You may need to make a small change to the visualisation before hand to make this a tad easier.

When creating a new variable we only care about the proportions of the two variables, so the intercept of the line can be ignored. I would suggest using a plot that shows and so you don’t have to constantly be adjusting the intercept of your line when you want to change the slope.

Using the plot of your data, there are two methods that can be used to find the slope () a line (this can be used reguardless of whether or not you are calculating the line that separates the two groups or the decision boundary). You can eyeball two points that should be on the line and use them to calculate . Since the decision boundary and the separating projection are perpendicular, you can swap between the two slops using the relationship .

Alternatively you can use geom_abline() from ggplot2 to plot the line with a slope of and an intercept of (assuming you shifted your data). Note, geom_abline() should only be used to check the decision boundary. Since the axis in the plot are scaled 10x:1y, the angle is severely warped and a right angle on the plane will not be a right angle in the data visualisation. Thereofre, the correct separating line will look very wrong when you draw it on the plot. By this same token, if you plot the decision boundary its associated 1D projection, they will not appear perpendicular.