library(tourr)

library(geozoo)

set.seed(1234)

cube3 <- cube.solid.random(3, 500)$points

cube5 <- cube.solid.random(5, 500)$points

cube10 <- cube.solid.random(10, 500)$pointsETC3250: Tutorial 3 Help Sheet

Exercises

Question 1

Randomly generate data points that are uniformly distributed in a hyper-cube of 3, 5 and 10 dimensions, with 500 points in each sample, using the cube.solid.random function of the geozoo package. What differences do we expect to see?

Check lecture 2 slide 18 for a visual of hypercubes in 2D space.

- How “cube like” do you expect the data to be when projected into 2D space?

- Do you expect the increasing dimensionality to affect that?

- The number of observations remains constant as we increase the sample size, what impact will that have?

Now visualise each set in a grand tour and describe how they differ, and whether this matched your expectations?

If you are running this code inside a QMD file, please make sure you have the chunk output option set to “in console”.

animate_xy(cube3, axes="bottomleft")

animate_xy(cube5, axes="bottomleft")

animate_xy(cube10, axes="bottomleft")Question 2

For the data sets, c1, c3 from the mulgar package, use the grand tour to view and try to identify structure (outliers, clusters, non-linear relationships).

animate_xy(c1)

animate_xy(c3)Check lecture 2 slide 21 and 22 to get an idea of how to comment on the structures you see in tours.

- How many clusters are there?

- How big are the clusters?

- How would you describe the shape of the clusters?

- How would you describe the overall shape of the data?

- How does the shape change as you move through different projections?

- Is there any statistical importance to some of the shapes you notice? (e.g. if the data can be projected into a straight line, what does that mean?)

Question 3

Examine 5D multivariate normal samples drawn from populations with a range of variance-covariance matrices. (You can use the mvtnorm package to do the sampling, for example.) Examine the data using a grand tour. What changes when you change the correlation from close to zero to close to 1? Can you see a difference between strong positive correlation and strong negative correlation?

library(mvtnorm)

set.seed(501)

s1 <- diag(5)

s2 <- diag(5)

s2[3,4] <- 0.7

s2[4,3] <- 0.7

s3 <- s2

s3[1,2] <- -0.7

s3[2,1] <- -0.7

s1

s2

s3

set.seed(1234)

d1 <- as.data.frame(rmvnorm(500, sigma = s1))

d2 <- as.data.frame(rmvnorm(500, sigma = s2))

d3 <- as.data.frame(rmvnorm(500, sigma = s3))

animate_xy(d1)

animate_xy(d2)

animate_xy(d3)Check lecture 2 slide 21 and 22 to get an idea of how to comment on the structures you see in tours.

- How does the shape of the data change as the correlation between the variables changes?

- How does this shape relate to the variance-covariance matrix?

- Look at the three variance-covariance matrices. Which variables have correlation in

s2ands3? What would you expect to happen when these variables are contributing to the projection?

Question 4

For data sets d2 and d3 what would you expect would be the number of PCs suggested by PCA?

The d2 and d3 data for this question is the same data used in the previous question (q3)

Check lecture 2 slide 29 to 34 to get an idea of how PCA works.

Answering these questions might be easier if we think about what will happen with d1, then compare d2 to d1, and then compare d3 to d2.

What would the PCA on a dataset with 5 uncorrelated variables look like? How many dimensions are needed to capture the variance of these 5 variables? Does capturing the variance get easier or harder when you correlate the variables?

We know that the PCA for d1, d2, and d3 will have 5 PCs simply because that is how many variables, but the question is moreso asking how many PCs will have “useful” information.

For d1, because there is no correlation, each variable needs to be captured separataly. You need one PC dimension to capture the variance in each of the 5 dimensions.

When you correlate two variables, you establish that those variables contain a lot of the same information and can be summarised together. That is, correlation should reduce the number of PCs requires to summarise the information in the data set.

Conduct the PCA. Report the variances (eigenvalues), and cumulative proportions of total variance, make a scree plot, and the PC coefficients.

To conduct the PCA, check lecture 2 slide 45 which calculates the PCA for an example. REMEMBER: All the columns in d2 and d3 are numeric with a mean of 0.

To report the variances, calculate how much of the variance is in the # of PCs you suggested in the previous part of this question. Lecture 2 slide 39 will give you the formula for proportion of total variance and cumulative variance.

Lecture 2 slide 47 has a scree plot but the code is not shown. Try downloading the lecture qmd file to find the code that made the scree plot.

The PC coeffieicnets are shown in lecture 2 slide 45. They are what is provided when you calculate the PCA.

Compute the PCA with prcomp(data)

If you name your prcomp, pca, you can get the proportion of variance explained for each PC using pca$sdev. Remember you total variance should be 5 due to standardisation.

Use mulgar::ggscree(pca, q=#variables) to make your scree plot

Often, the selected number of PCs are used in future work. For both d3 and d4, think about the pros and cons of using 4 PCs and 3 PCs, respectively.

Based on the response you gave at the begining of this question, what do you think an ideal PC for d1, d2 and d3 would look like? How do the actual PCs differ from that solution? How does this impact the number of PCs you should use in your work?

Question 5

The rates.csv data has 152 currencies relative to the USD for the period of Nov 1, 2019 through to Mar 31, 2020. Treating the dates as variables, conduct a PCA to examine how the cross-currencies vary, focusing on this subset: ARS, AUD, BRL, CAD, CHF, CNY, EUR, FJD, GBP, IDR, INR, ISK, JPY, KRW, KZT, MXN, MYR, NZD, QAR, RUB, SEK, SGD, UYU, ZAR.

Part A

Standardise the currency columns to each have mean 0 and variance 1. Explain why this is necessary prior to doing the PCA or is it? Use this data to make a time series plot overlaying all of the cross-currencies.

rates <- read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/numbats/iml/master/data/rates_Nov19_Mar20.csv") |>

select(date, ARS, AUD, BRL, CAD, CHF, CNY, EUR, FJD, GBP, IDR, INR, ISK, JPY, KRW, KZT, MXN, MYR, NZD, QAR, RUB, SEK, SGD, UYU, ZAR)library(plotly)

rates_std <- rates |>

mutate_if(is.numeric, function(x) (x-mean(x))/sd(x))

rownames(rates_std) <- rates_std$date

p <- rates_std |>

pivot_longer(cols=ARS:ZAR,

names_to = "currency",

values_to = "rate") |>

ggplot(aes(x=date, y=rate,

group=currency, label=currency)) +

geom_line()

ggplotly(p, width=400, height=300)Check lecture 2 slide 45. Were the variables in that data set standardised before the PCA was calculated?

Setting scale=TRUE means we don’t need to standarise the variables for the computation of the PCA, however you should consider what will happen to the time series plot if we don’t standardise the variables beforehand.

A time series plot would require a ggplot() with x=date, y=rate, and group=currency. Consider using pivot_longer() to get your data in a form where it is easy to plot.

Part B

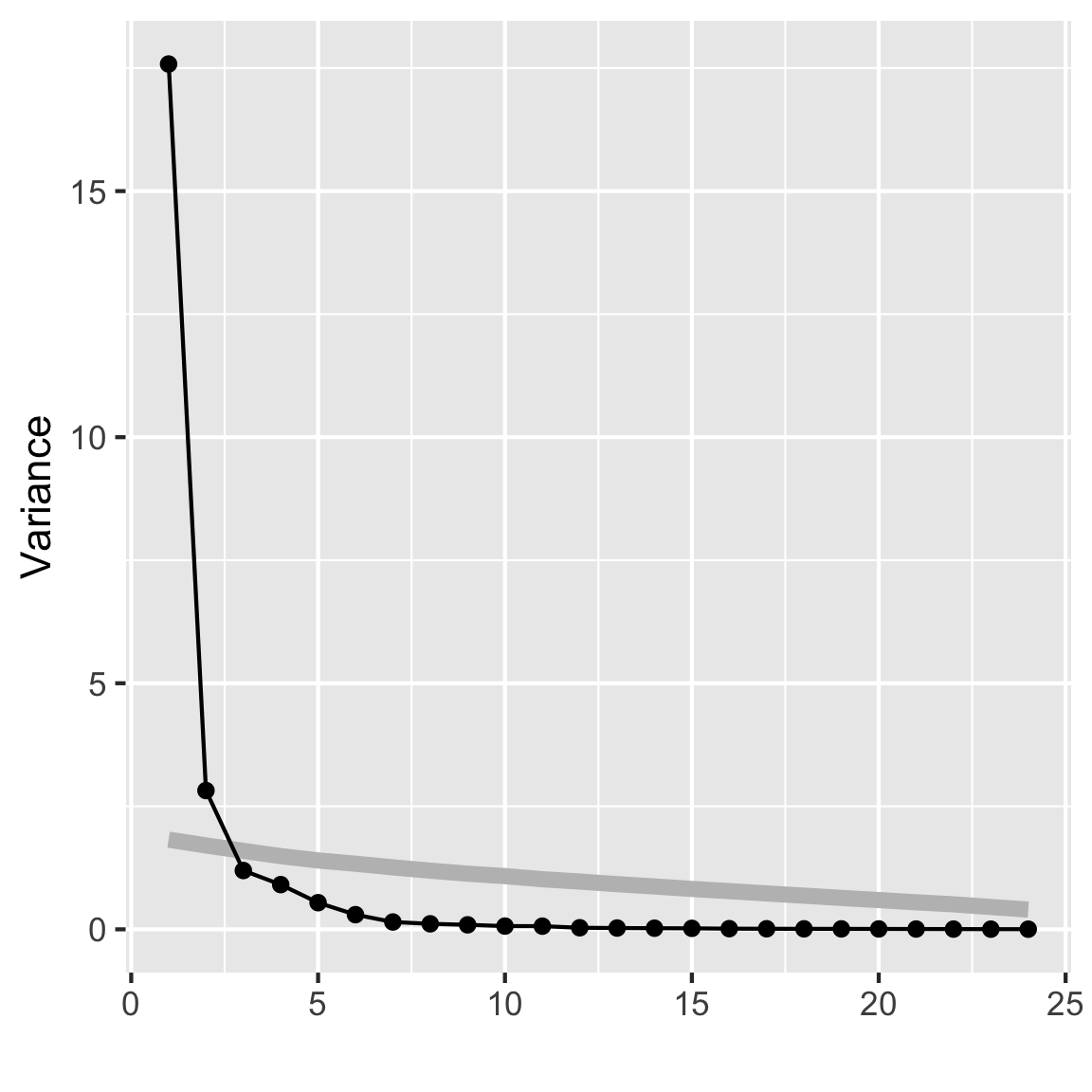

Conduct a PCA. Make a scree plot, and summarise proportion of the total variance. Summarise these values and the coefficients for the first five PCs, nicely.

The following hints are identical to those in question 4 that are for the computation.

To conduct the PCA, check lecture 2 slide 45 which calculates the PCA for an example. REMEMBER: All the columns in d2 and d3 are numeric with a mean of 0.

To report the variances, calculate how much of the variance is in the # of PCs you suggested in the previous part of this question. Lecture 2 slide 39 will give you the formula for proportion of total variance and cumulative variance.

Lecture 2 slide 47 has a scree plot but the code is not shown. Try downloading the lecture qmd file to find the code that made the scree plot.

The PC coeffieicnets are shown in lecture 2 slide 45. They are what is provided when you calculate the PCA.

Compute the PCA with prcomp(data)

If you name your prcomp, pca, you can get the proportion of variance explained for each PC using pca$sdev. Remember you total variance should be 5 due to standardisation.

Use mulgar::ggscree(pca, q=#variables) to make your scree plot

rates_pca <- prcomp(rates_std[,-1], scale=FALSE)

mulgar::ggscree(rates_pca, q=24)

options(digits=2)

summary(rates_pca)Importance of components:

PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6 PC7 PC8

Standard deviation 4.193 1.679 1.0932 0.9531 0.7358 0.5460 0.38600 0.33484

Proportion of Variance 0.733 0.118 0.0498 0.0379 0.0226 0.0124 0.00621 0.00467

Cumulative Proportion 0.733 0.850 0.8999 0.9377 0.9603 0.9727 0.97893 0.98360

PC9 PC10 PC11 PC12 PC13 PC14 PC15

Standard deviation 0.30254 0.25669 0.25391 0.17893 0.16189 0.15184 0.14260

Proportion of Variance 0.00381 0.00275 0.00269 0.00133 0.00109 0.00096 0.00085

Cumulative Proportion 0.98741 0.99016 0.99284 0.99418 0.99527 0.99623 0.99708

PC16 PC17 PC18 PC19 PC20 PC21 PC22

Standard deviation 0.11649 0.10691 0.09923 0.09519 0.08928 0.07987 0.07222

Proportion of Variance 0.00057 0.00048 0.00041 0.00038 0.00033 0.00027 0.00022

Cumulative Proportion 0.99764 0.99812 0.99853 0.99891 0.99924 0.99950 0.99972

PC23 PC24

Standard deviation 0.05985 0.05588

Proportion of Variance 0.00015 0.00013

Cumulative Proportion 0.99987 1.00000# Summarise the coefficients nicely

rates_pca_smry <- tibble(evl=rates_pca$sdev^2) |>

mutate(p = evl/sum(evl),

cum_p = cumsum(evl/sum(evl))) |>

t() |>

as.data.frame()

colnames(rates_pca_smry) <- colnames(rates_pca$rotation)

rates_pca_smry <- bind_rows(as.data.frame(rates_pca$rotation),

rates_pca_smry)

rownames(rates_pca_smry) <- c(rownames(rates_pca$rotation),

"Variance", "Proportion",

"Cum. prop")

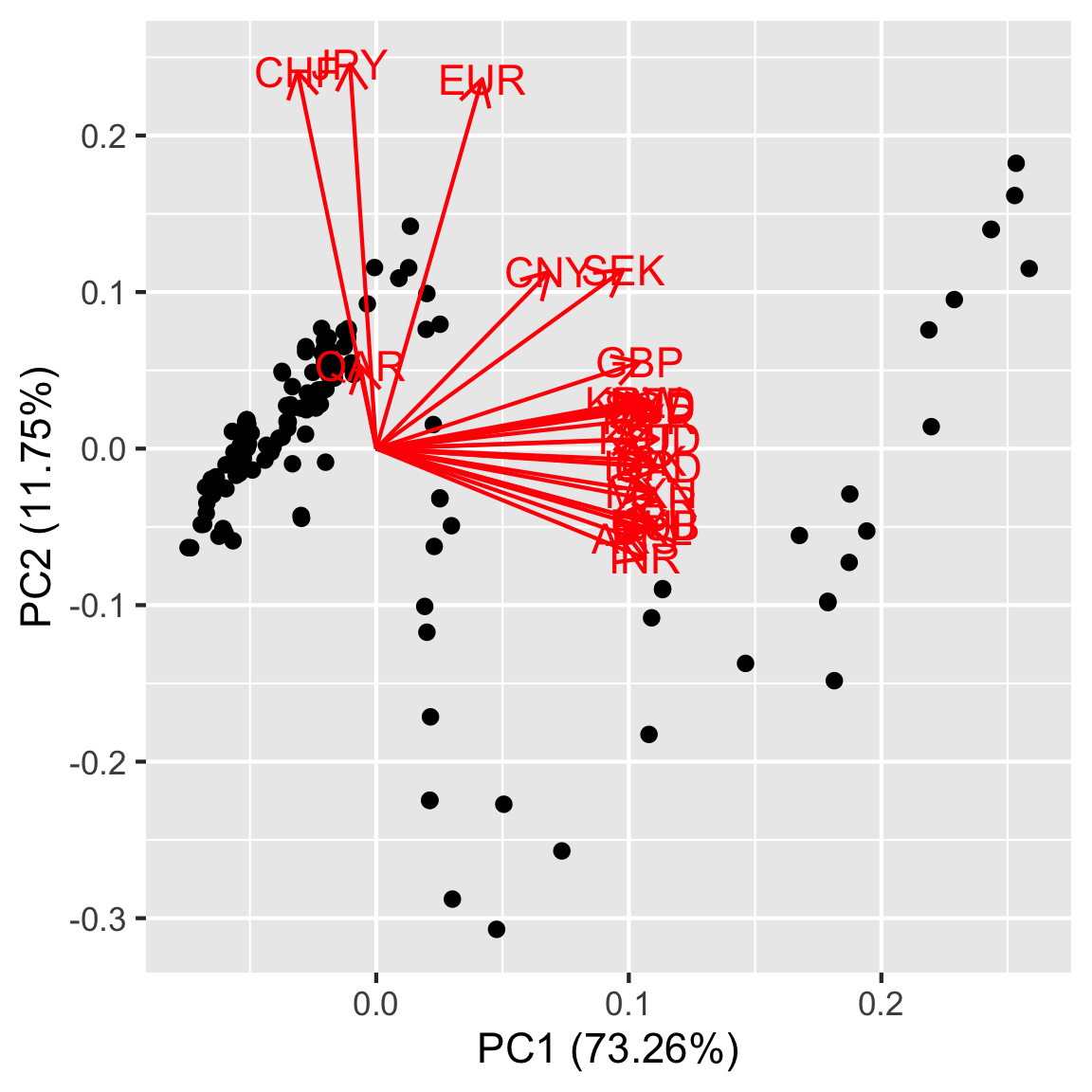

rates_pca_smry[,1:5] PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5

ARS 0.215 -0.121 0.19832 0.181 -0.2010

AUD 0.234 0.013 0.11466 0.018 0.0346

BRL 0.229 -0.108 0.10513 0.093 -0.0526

CAD 0.235 -0.025 -0.02659 -0.037 0.0337

CHF -0.065 0.505 -0.33521 -0.188 -0.0047

CNY 0.144 0.237 -0.45337 -0.238 -0.5131

EUR 0.088 0.495 0.24474 0.245 -0.1416

FJD 0.234 0.055 0.04470 0.028 0.0330

GBP 0.219 0.116 -0.00915 -0.073 0.3059

IDR 0.218 -0.022 -0.24905 -0.117 0.2362

INR 0.223 -0.147 -0.00734 -0.014 0.0279

ISK 0.230 -0.016 0.10979 0.093 0.1295

JPY -0.022 0.515 0.14722 0.234 0.3388

KRW 0.214 0.063 0.17488 0.059 -0.3404

KZT 0.217 0.013 -0.23244 -0.119 0.3304

MXN 0.229 -0.059 -0.13804 -0.102 0.2048

MYR 0.227 0.040 -0.13970 -0.115 -0.2009

NZD 0.230 0.061 0.04289 -0.056 -0.0354

QAR -0.013 0.111 0.55283 -0.807 0.0078

RUB 0.233 -0.102 -0.05863 -0.042 0.0063

SEK 0.205 0.240 0.07570 0.085 0.0982

SGD 0.227 0.057 0.14225 0.115 -0.2424

UYU 0.231 -0.101 0.00064 -0.053 0.0957

ZAR 0.232 -0.070 -0.00328 0.042 -0.0443

Variance 17.582 2.820 1.19502 0.908 0.5413

Proportion 0.733 0.118 0.04979 0.038 0.0226

Cum. prop 0.733 0.850 0.89989 0.938 0.9603Part C

Make a biplot of the first two PCs. Explain what you learn.

Lecture 2 slide 48 has a biplot but the code is not shown. Try downloading the lecture qmd file to find the code that made the scree plot.

library(ggfortify)

autoplot(rates_pca, loadings = TRUE,

loadings.label = TRUE)

- Is there any noticeable shape? Does that shape make sense given what you know about biplots?

- Which variables contribute to PC1? What about PC2?

- Given which countries contribute to each PC, is there any real world effect that you think the data is picking up on?

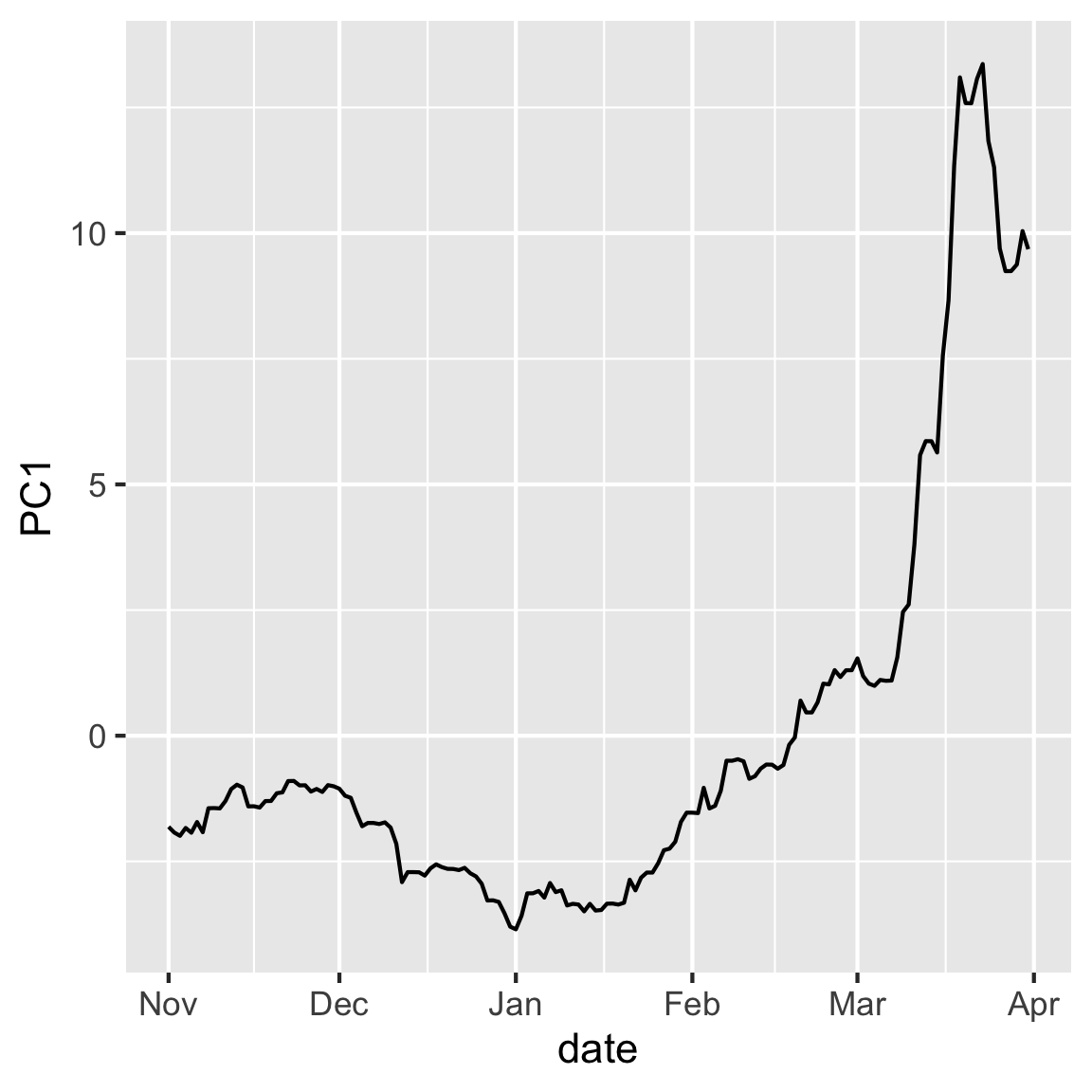

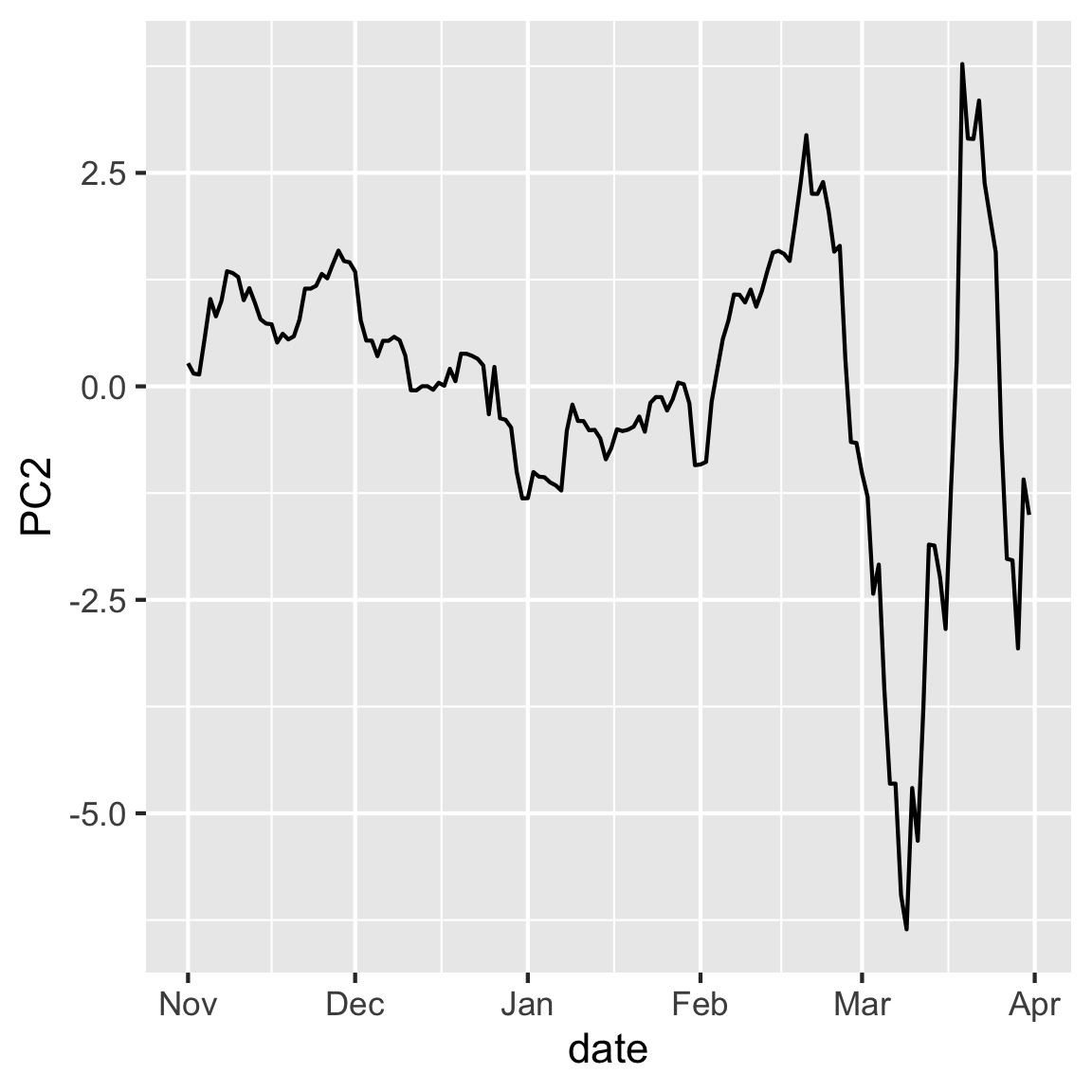

Part D

Make a time series plot of PC1 and PC2. Explain why this is useful to do for this data.

rates_pca$x |>

as.data.frame() |>

mutate(date = rates_std$date) |>

ggplot(aes(x=date, y=PC1)) + geom_line()

rates_pca$x |>

as.data.frame() |>

mutate(date = rates_std$date) |>

ggplot(aes(x=date, y=PC2)) + geom_line()

- Is there any inherent structure in the observation in this case? How might that structure impact your interpretation of the PCs?

- Do you notice any patterns in the data when you plot them according to your PCs?

- These values are relative to the USD, are the patterns in the data expected given the currencies that contributed to each PC?

Part E

You’ll want to drill down deeper to understand what the PCA tells us about the movement of the various currencies, relative to the USD, over the volatile period of the COVID pandemic. Plot the first two PCs again, but connect the dots in order of time. Make it interactive with plotly, where the dates are the labels. What does following the dates tell us about the variation captured in the first two principal components?

library(plotly)

p2 <- rates_pca$x |>

as.data.frame() |>

mutate(date = rates_std$date) |>

ggplot(aes(x=PC1, y=PC2, label=date)) +

geom_point() +

geom_path()

ggplotly(p2, width=400, height=400)- Are the PCs related to time? What time periods cause changes in the pattern?

- Try to think about real world events that correlate with the dates that you have in your pattern.

Question 6

Write a simple question about the week’s material.